Where the apostle Paul explicitly calls Jesus God

Paul, at 1 Corinthians 8:6, expands the well known passage from Deuteronomy 6:4 and inserts Jesus. In writing to the Corinthians Paul is redefining monotheism as Christ-centred monotheism.

You should know who Granville Sharp is

Granville Sharp, was one of the first British campaigners for the abolition of the slave trade. Along with being a musician and classicist, Sharp was also a brilliant Greek grammarian and biblical scholar. Yesterday, Nov. 10th, was his birthday.

Luther (probably) didn't nail the 95 Theses

One of the most famous catalysts for the start of what eventually became known as the Protestant Reformation was Luther’s 95th Thesis, which were famously reported to have been nailed to the Castle Church in Wittenberg, on October 31st, 1517…

Who took verses out of your Bible?

If you open up to nearly all modern English translations of the Gospel of John, at 5:4 you’ll notice something conspicuous. It goes from verse 3 to verse 5. So who took out verse 4? The answer to that question leads us back to the earliest surviving copies of John. Copies like our two 3rd century manuscripts of John like P75 and P66…

Ancient manuscripts made from snail spit

This is a 6th century Greek New Testament and one of the “purple codices.” Its pages are velum (calf skin), dyed purple, with both silver and gold leaf used for the lettering…

What is the "Jesus fish?"

This is P.Oslo Inv. 303, a manuscript from the 4th century that acted as a Christian amulet. It is written in Greek and was used as an invocation to ward off evil from the household. This type of written appeal was popular in Egypt throughout antiquity. The inscription ends with an Alpha Cross Omega, Symbol of Christ, and the word Ichthus (Ίχθύς).

How ancient toilet paper might help us understand Paul

The ultimate fate of P.Oxy4633, a 3rd century papyrus commentary on Homer, a part of the Oxyrhynchus collection, was…. toilet paper.

What is the Gospel of Jesus' Wife?

10 years ago, Dr. Karen King, a senior Harvard historian in early Christianity, gave an announcement across from the Vatican that an ancient papyrus in which Jesus speaks of “his wife” had just been discovered…

The British Monarchy and the most famous English Bible

The King James Bible was commissioned in 1604 and published in 1611. The beginning of it had a dedication to the King of England. James was potentially the most scholarly king to ever sit on the English throne. He produced his own commentary/paraphrase of Revelation, and even his own translation of the Psalms…

Is the number of the beast REALLY 666?

Everyone knows the number of the beast from the biblical book of Revelation, right?It’s 666. That’s just common knowledge! Or is it…

Why is Michelangelo's Moses horned?

Because of the Latin Vulgate's (the Latin translation of the Bible that stood as the Bible of the church for a thousand years) influence we have portrayals all throughout the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance like that of Michelangelo’s statue of Moses, which is horned

Archeaology of Roman brothels, moral quandries, and baby corpses

Brothels were common place within antiquity and were often placed between houses of respected Roman families. Far from being perceived as taboo, brothels were one of the most common gathering places for Roman men. It was seen as antisocial for men not to engage in activities with prostitutes…

Relevant sources:

Harris, W. V. “Child-Exposure in the Roman Empire.” The Journal of Roman Studies 84 (1994): 1–22. Shaw.

Brent D., Raising and Killing Children: Two Roman Myths, Fourth Series, Vol. 54, Fasc. 1 (Feb., 2001), pp. 31-77.

Brill. H. Bennett, "The Exposure of Infants in Ancient Rome" The Classical Journal, Vol. 18, No. 6 (Mar., 1923), pp. 341-351 (11 pages) John Hopkins University Press. Crook.

John, Patria Potestas. Vol. 17, No. 1 (May, 1967), pp. 113-122 (10 pages), Cambridge University Press. Boswell.

John Eastburn. ìExpositio and Oblatio: The Abandonment of Children and the Ancient and Medieval Family,î American Historical Review 89 (1984): 10-33.

Dixon, Suzanne. The Roman Family. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992. Golden, Mark ìDemography, The Exposure of Girls at Athens,î Phoenix 35 (1981): 316-331.

Golden, Mark ìDemography, Did the Ancients Care When Their Children Died? Greece & Rome 35 (1988): 152-163.

O. M. Bakke, "When Children Became People: The Birth of Childhood in Early Christianity," 2005. Rawson, Beryl, Children and Childhood in Roman Italy. Oxford: Oxford University., Press, 2003.

https://bonesdontlie.wordpress.com/2011/08/18/the-babies-and-the-brothel/

https://www.bbc.com/news/10384460 https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna42911813

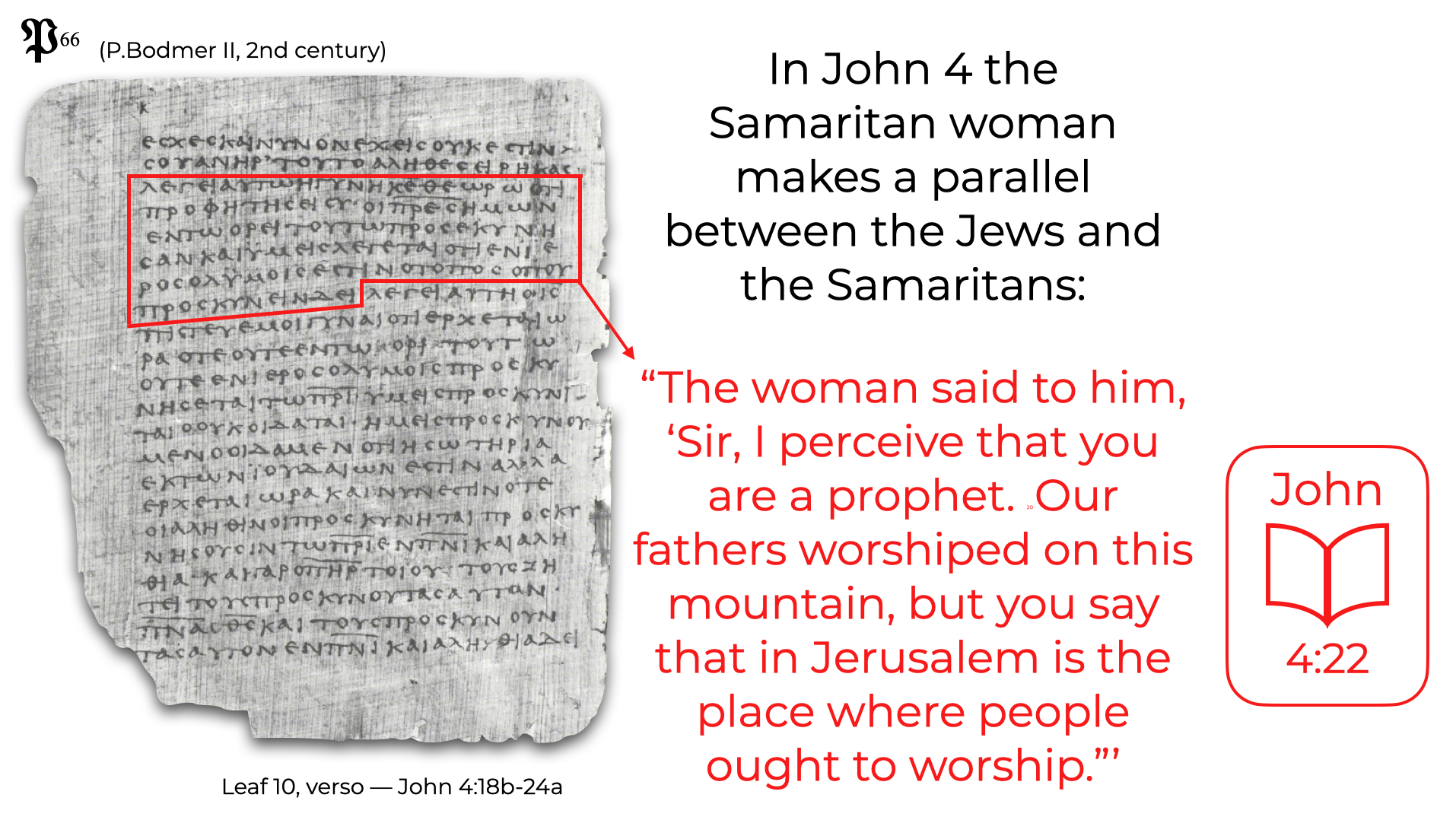

Manuscripts confirming Jesus, Josephus, and the Woman at the Well

In John 4 we have the story recorded for us of a conversation between Jesus and a Samaritan woman at a well in the land of Samaria. During the course of the conversation Jesus makes a very strange statement…

Some of the most ancient and most notable New Testament manuscripts

P52 (aka John Rylands 457) is one of the most notable New Testament manuscript fragments. Potentially the earliest extant piece of documentary evidence for the biblical New Testament, this papyrus fragment was discovered by C.H. Roberts in the basement of the John Rylands Library in 1934.

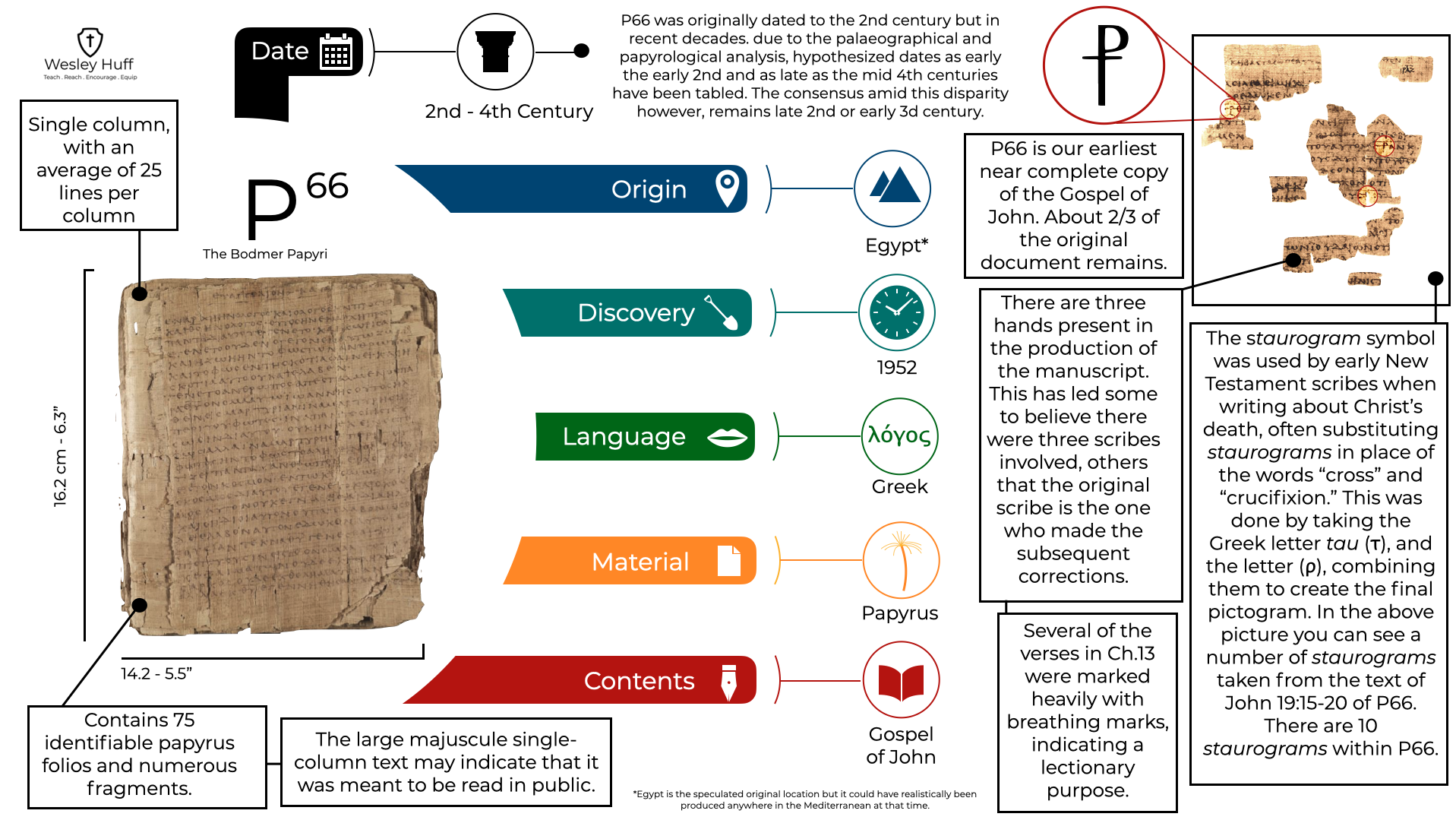

P66 (aka P.Bodmer II) is one of the earliest and most well preserved copies of the Gospel of John. Containing 2/3 of the entire Gospel, its discovery and publication surprised scholars due to the first 26 leaves being almost entirely intact. Ancient codices (what we would think of as a book) tend to lose most of the top and bottom sheets due to those being the most vulnerably exposed. Dated as early as the second century and as late as the fourth century, it nonetheless is in incredible shape considering its age. P66 is currently housed at the Bibliotheca Bodmeriana, in Cologny, just outside Geneva.

P75 (aka Papyrus Bodmer XIV XV) is a 2nd or 3rd century manuscript text of Luke and John. Owned originally by Martin Bodmer and later donated to the Vatican where it is housed to this day. The text of P75 has a striking similarity to the 4th century Codex Vaticanus, which when discovered and evaluated, opened up a conversation both the scholarly perception of the text in its early form and as well as the function and purpose of Codex Vaticanus as a major codex.

P46 (aka P. Chester Beatty II), was discovered somewhere in the Fayum of Egypt, near what is beleived to be the ruins of a monastery near Atfih. It is one of our earliest collection manuscripts, that is, instead of being a single independent document it is a grouping of the Pauline epistles. Very early on the four Gospels and the Pauline epistles were being grouped together in collection codices, pointing to their significance in the early Christian community as prominent and important writings. One significance to this is that the P46 collection includes the book of Hebrews. While the majority of modern scholarship (correctly in my opinion) believes that Hebrews was not in fact written by Paul, it does appear that the collector of P46 did.

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

Codex Sinaiticus (aka א) is one of the most important Bibles in the world. The project started in the Middle of the fourth century and it marks our earliest surviving complete copy of the Christian New Testament in one volume. Having been in regular use for what is estimated to be around 600 years, Sinaiticus was eventually rediscovered at the Monastery of St. Catherine, at the base of Mount Sinai, in the nineteenth century by German biblical scholar, Constantine Tischendorf.

Codex Vaticanus ( aka B ) is one of the most important Bible’s in the world. The document has been housed in the Vatican Library since the 16th century and was largely made known to the world of Western biblical scholarship due to Erasmus’ correspondence with Bombasius in Rome in order to consult this important 4th century manuscript. Erasmus did so in order to see whether 1 John 5:7-11 was included in the most ancient readings of 1 John. The reading was not and so Erasmus (rightly) left it out of his 1st and 2nd editions of his Greek New Testaments. The 3rd edition did include 1 John 5:7-11 but this was largely due to pressure from the church authority at the time. Erasmus’ 3rd edition played a key role as an early edition of the primary texts used by the KJV translators and is one of the main reasons why 1 John 5:7-11 is in the King James today but not in modern translations.

What are the Biblical Autographs?

With a desire to defend a high view of Scripture, potentially in juxtaposition to an increasing skepticism towards the Bible over the last century or so, the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy, a theological Statement formed in 1978, states in Article X that:

“We affirm that inspiration, strictly speaking, applies only to the autographic text of Scripture,which in the divine providence of God can be ascertained from available manuscripts with great accuracy. We further affirm that copies and translations of Scripture are the Word of God to the extent that they faithfully represent the original.”

This is an important and carefully crafted statement. However, in many theological, apologetical, and biblical discussions, the term “autograph” and “original text” has been used in ways that they were never intended by the scholars who coined the terms in the first place.

The autograph

Some have argued that there is no use to say “the originals were inspired or inerrant” if we no longer have the originals. As one popular pastor put it recently in a video commenting on how he understood the term “inerrant”:

“[T]he doctrine of inerrancy only applies to the original autographs, the original copies — which we don’t have any more. But we do have a number of early copies, enough to get us pretty close to what the originals would have said; but it raises the question, if God didn’t preserve the originals did his inspiring and preserving work of the Holy Spirit apply to the copying process over hundreds and hundreds of years?”

This would be a plausible statement if what scholars meant by “the original autograph/text” was the physical document that the initial author wrote on. The problem with such a statement is that is almost entirely not what is meant when scholars refer to these very specific terms.

Doctrinal statements, apologists, and theologians are, on the whole, wise to point out that authorial copies of the New Testament are distinguished from subsequent various textual forms and alterations introduced throughout the decades, centuries, and millennia since their inception.

The doctrines of inspiration, inerrancy, and infallibility are not fundamentally affected by textual variances throughout the manuscript tradition. This is both an accurate and attentive feature to highlight. At the same time however, these same individuals often conflate the autographs as physical artifacts and the text of the autographs themselves.

Physical copies and their words

Within the contemporary Christian world we need to be careful to distinguish between the autographs as the first written copies and the words on those copies. Scholars who work within the field of ascertaining the original text of Scripture have less interest in the physical material (i.e. the papyrus, vellum, or parchment) than they do with the text found on them (there are entirely separate disciplines that study the physical materials such as papyrology and palaeography).

Therefore, when textual critics refer to the “original text” or “original autographs” they may be (but probably are not) talking about the material document as much as they are the original wording on the original document. This is a point that the Chicago Statement does a good job of highlighting when it states that inspiration, “applies only to the autographic text of Scripture.”

The origin of the confusion partly sits at the feet of the scholars who use these technical terms. Sometimes scholars do not succinctly define their terminology when using such phrases as “original text” or “original autograph”. Therefore, when popular level writers, pastors, defenders of the faith, even professional apologists and scholars in adjacent fields, read or hear about the “original autographs” or “original text” they may assume that what is in focus are the first copies of a said document — but that is hardly ever if at all the case.

In fact, if you have been following the field of New Testament textual criticism as of late you will have noticed that the designation “autograph” (or its German originator autographa) has become somewhat of an outdated term. There are many reasons for this, whether that be a growing suspicion in recent scholarship as to whether one can truly derive the original text or whether it is in an effort to not confuse the physical document of the autograph with the original text on the autograp.

The question is: if “all Scripture is God breathed” (2 Tim. 3:16), did God breath into the papyrus or leather, or is it the words, message, meaning, and intention of Scripture that was divinely inspired? We as modern Christians can stand in a long line of succession with theologically minded believers throughout history in saying that it is not the material that is the focal concern but the text found on said material.

God has inspired, preserved, and given to us His Word which is sufficient as the sole infallible rule of faith and practice for the church. Any dispersion on the inspiration, reliability, and trustworthiness of Scripture on the basis of not possessing “the originals” falls flat. It does so because we have incredible confidence that we know what the words on those originals were to begin with.

For more related to this topic read:

One Bible, Many Versions

Were the Gospels Anonymous?

Why Trust the Bible? (P.1)

Why Trust the Bible? (P.2)

Did Jesus Speak Greek?

What happened at the Council of Nicaea?

Why I date the Gospel of Thomas late?

First Century Mark - Fragments and Figments of our Imagination

Were the Gospels anonymous?

The majority of modern New Testament scholarship today believe that the canonical Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) were originally penned and circulated anonymously. The thinking being that these documents were what is sometimes referred to as being “formally anonymous,” in that, if you removed the “Gospel According to …” title from the front page and remained with the content you would not necessarily know who the author was. New Testament scholar Rudolf Pesch notes in his commentary on the Gospel of Mark that the “Gospel of Mark was without doubt published anonymously… all inscriptions and subscriptions in the Gospel manuscripts are late.” As Richard Backham notes:

“The assumption that Jesus traditions circulated anonymously in the early church and therefore the Gospels in which they were gathered and recorded were also originally anonymous was very widespread in twentieth-century Gospel scholarship. It was propagated by the form critics as a corollary to their use of the model of folklore, which is passed down anonymously by communities. The Gospels, they thought, were folk literature, similarly anonymous. This use of the model of folklore has been discredited… partly because there is a great difference between folk traditions passed down over centuries and the short span of time — less than a lifetime — that elapsed before Gospels were written. But it is remarkable how tenacious has been the idea that not only the traditions but the Gospels themselves were originally anonymous.”

(Bauckham, Richard, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2006), 300.)

The tenaciousness that Bauckham mentions was indeed the reality of twentieth century New Testament scholarship. This of course is not limited to the past century, as testified by Pesch’s statement. However, the confidence of scholars like Pesch I believe exceeds what the evidence actually indicates. To say that it is “without doubt” that Mark was published anonymously is a very big statement given the fact that the evidence for it seems to be mixed.

This is not to say that Pesch and the majority of scholars’ assertions regarding Gospel authorship and anonymity could not be true. It could be. Majority views are important, and so, if one is going to make an assertion to the contrary of the majority view there better be good reason and sufficient evidence pointing towards that case. The question then is where does the preponderance of evidence point when it comes to Gospel anonymity and what should our conclusions be from said evidence?

What if they were anonymous?

Here’s the reality: if the Gospels were penned anonymously not that much would truly be impacted. A good many works from antiquity are formally anonymous. Other documents within the Christian Scriptural canon are anonymous. 1st and 2nd Chronicles and 1st and 2nd Kings from the Old Testament or the book of Hebrews from the New Testament, all formally anonymous. Not knowing the identity of the author of these books in no way jeopardizes their authority or credibility. From outside the Scriptures themselves we have the works of Philo of Alexandria, the famous Jewish thinker from the first century BC, are written with no formal mention of the author’s name within the document. If the Gospels were written in this way it would not jeopardize the reliability of their content. There are many internal and external methods of verification to identify the biblical Gospels as early, eyewitness-based accounts of the life of Jesus of Nazareth— with or without a direct ascription to who the author was or wasn’t.

No originals

We are also left with the reality that every writing from the ancient world falls into — we do not possess the original copies. The collection of writings we call the New Testament are approximately two thousand years old and the originals documents that the authors penned have been lost to the sands of time. With the loss of the originals we also have the disappearance of any first-hand evidence that they were or were not titled with the authors name. For this reason it cannot be known whether Matthew, Mark, Mark, Luke, or John inscribed a title to his Gospel account or not.

Author identities

It cannot be discounted that at least two of the Gospel accounts, Mark and Luke, have traditional ascription to non-disciples. If the Gospels did circulate anonymously in their earliest forms then why eventually assign names of particularly unimpressive characters to them? Why not vouch for and chose individuals who had early and widely accepted notoriety as key individuals within the Jesus community? Neither Mark nor Luke had an outstanding reputation as particularly noteworthy individuals. Both individuals in their respective identification traditions have links to others. Mark’s Gospel is reported to have found his source material in Peter. Why not then call this account The Gospel of Peter? If a Gospel account is anonymous why then almost unanimously settle on Mark, the cousin of Barnabas, who deserted the first missionary journey with Paul and went home (Acts 13:13, 15:37-39)?

This could even be argued for Matthew, a character about whom almost nothing is known and whose only claim to fame (outside of penning the Gospel) is that he was a tax collector in the Gospel narratives. Tax collectors were not exactly the most popular of Characters in first-century Roman occupied Galilee. So to choose Matthew over and above other characters within the narrative seems odd. Why not select clearer heavy hitters? Why not associate the earliest narrative accounts of Jesus with weightier apostolic authority? Especially, and with particular note, to the other Gospels that start to pop-up in the second century and following which make explicit claims to the authorship of characters like Philip, Mary, Peter, and Thomas.

Why do any of that, unless of course, the traditional attributions were in fact the authors?

Consistency in Titles

The strongest evidence against traditional authorship being straightforward would be the earliest manuscripts themselves showing diversity in attribution of the author. For example, if we were to find multiple copies with the text of what we now call the Gospel of Matthew with a different title, say, the text of the Gospel of Matthew with a heading of the Gospel of Peter, or the Gospel of John, then this would be warrant for pause. The problem however, is that we find no such thing. There are no competing claims of titled authorship in any of the manuscripts that survive with a title heading. In every single text that we have where the beginning or the ending of the work survives (the two places we find such titled inscriptions), we find the traditional authorship assigned.

These surviving copies are rare, granted, but not unprecedented. P75, for example, which dates somewhere in the mid to late second century, on leaf 47 (recto) has a very clear “εὐαγγελίον κατα Λουκᾶν” (“Gospel According to Luke”) at the end of the book (Luke 24:53).

Manuscript photograph of P75 courtesy of CSNTM’s Manuscript database. Original manuscript is housed in the Vatican Library (Pap. Hanna. 1).

Although not as nicely preserved in its incipit, another second century Gospel, P66, begins with the title “εὐαγγελίον κατα Ἰωάννην” (“Gospel according to John).

Manuscript photograph of P66 courtesy of CSNTM’s Manuscript database. Original manuscript is housed in at Foundation Martin Bodmery (Université de Genève in Geneva, P.Bodmer II).

All of our major Codices from the fourth and fifth centuries likewise include (at either the very beginning of the very end) an identifier of the author with the traditional name associated with the document. There has yet to be discovered a copy of a biblical Gospel with an inscription of a different name other than the traditional author.

The Manuscript Evidence: No Anonymous Gospels

Pitre, Brant, The case for Jesus: The biblical and historical evidence for Christ (New York: Penguin house Llc, 2016), 17.

What does all this mean?

Where this leaves us is with, in my estimation, relatively sound evidence to conclude that the names of the four canonical Gospels are indeed the authors. Although the early church testimony to these authors was not necessarily discussed in this particular blog, this early testimony also adds to the verification of the authors being the namesakes we associate with those particular documents. Of course it is theoretically possible that these documents were originally circulated anonymously, from the estimation of the evidence I do not believe that to be the case.

For more:

What Happened at the Council of Nicaea?

It’s a common accusation, “the books of the Bible were chosen at the Council of Nicaea.”

I have read it in books and internet forums as well as heard it from laypeople and academics. It is a line that has been repeated over and over, having taken on a life of its own due to the popularity of Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code and the explosion of promulgation due to the internet.

One of the main characters in the Da Vinci Code, Leigh Teabing, states at one point that, “Constantine commissioned and financed a new Bible, which omitted those gospels that spoke of Christ’s human traits and embellished those gospels that made him godlike” (Brown, 325). These sort of ideas didn’t start with Dan Brown, the story in one form or another has been floating around for decades and even centuries before any such works of popular fiction. So the valid question that follows is: what did happen at the Council of Nicaea?

What happened at Nicaea?

The first Council of Nicaea, which took place between May and August in 325 AD in what is now İznik, Turkey, was an ecumenical council called to deal with a specific theological problem. Its purpose was to sort out the Arian Controversy––a Trinitarian heresy being promoted by a presbyter in North Africa named Arius, teaching not only that the Son of God was eternally subordinate to the Father, but that the Son was not everlasting but created by God the Father at a specific point in time. Arius, in his letter to Alexandria, wrote that: “The Son, being begotten apart from time by the Father, and being created and founded before ages, did not exist before his generation… the Son is not eternal or co-equal or co-unoriginate with the Father” (Letter to Alexandria 4:458).

There is even a story that developed later that St. Nicholas (yes, good St. Nick himself), struck Arius in the face during Nicaea after Arius stood up and uttered his famous statement that, “there was a time when the Son was not.” While the visual of Santa punching heretics in the face makes for a good laugh and a fun story, the narrative developed later and cannot legitimately be tied to anything that actually happened historically at the council.

The end result of the assembly was what is now known as the Nicene Creed, along with twenty canon decrees and a synod epistle that went along with the creedal statement. Within all of these documents, Nicaea quotes the New Testament books as authoritative and acknowledged the supremacy and jurisdiction they held. All 318 members (even the unorthodox ones as far as we can tall) recognized the rule scripture possessed already, they did not invent the status it held. The twenty-seven books of the New Testament were being read, studied, preached, and declared as God’s holy Word hundreds of years before anyone at Nicaea was even born.

There is no evidence from any of the documents that came out of Nicaea nor from the testimony of witnesses and members who were there (Eusebius, Athanasius, or Eustathius, for example) that any part of the council had anything to do with choosing or establishing the canon of Scripture. So where did this idea originate from? Well, there are two possible sources where the myth could have originated and taken on a life of its own.

One of these options has ancient origins with the other being a little more contemporary. The first comes from a line in the commentary on Judith by Jerome (347–420 AD). In the preface to his work on Judith, Jerome states: “But since the Nicene Council is considered to have counted this book among the number of Scriptures, I have acquiesced to your request (or should I say demand!).”

It is important to note that Jerome’s statement does not necessarily mean that Nicaea chose books but could have merely discussed the topic and in the framework of that discussion included writings some may have considered Scripture. That does not mean they were Scripture and certainly doesn’t mean they bestowed any such documents with the authority of Scripture. The content of this single quote is a far cry from any type of vote, of which we have no evidence for. It is also key to take note that other key players present at Nicaea like Athanasius, Gregory of Nazianzus, and Hilary of Poitiers, all rejected Judith as canonical Scripture in their subsequent canon lists.

Judith likewise, is quite an odd candidate as it contains numerous blatant historical errors (saying Nebuchadnezzar was “king of Nineveh,” not of Babylon, for example) that both Jews and Christians over the centuries have pointed out as highly problematic. Given all of the evidence of what we can see definitively did take place at Nicaea, it is also possible that Jerome was simply incorrect, or that his statement did not intend to point to an instance of a vote of choice, but rather, a discussion that included books others supposed held some authority (for more on Jerome’s intentions see Ed Gallagher’s article in the Harvard Theological Review). Whatever the case this may or may not be where the first echoes of the whole “the Bible was chosen at Nicaea” started. Personally, however, I don’t think that’s where it came from. I think that the account derives its origins from a source a little closer to our time than Jerome of Stridon.

The Modern Nicaea Myth

Unlike a passing comment from Jerome, the way the narrative is so definitively presented in many modern forms appears to be from a pseudo-historical ninth-century Greek manuscript known as the Synodicon Vetus. The Synodicon Vetus claims to present information on church councils and synods from the first to the ninth centuries. At the section regarding Nicaea it says the following: “The council made manifest the canonical and apocryphal books in the following manner: placing them by the side of the divine table in the house of God, they prayed, entreating the Lord that the divinely inspired books might be found upon the table, and the spurious ones underneath; and it so happened.”

According to this document the source of what we now know as the New Testament canon originates from a miracle that took place when those present at Nicaea prayed over a collection of canonical and apocryphal books. The claim by this narrative is that the documents that were indeed “divinely inspired books” stayed on the table and those that were “spurious” found their way underneath it by miraculous means.

The Synodicon Vetus then appears to have been passed through the hands of a number of individuals over the centuries; the original Greek document eventually making its way into the possession of an individual named Andreas Darmasius in the sixteenth century. It was subsequently bought, edited, printed, and published by a German man at the beginning of the seventeenth century named John Pappus.

Pappus’ publication made its way into the hands of none other than the French Enlightenment thinker Voltaire, in the late seventeenth century. In Vol. 3 of Voltaire’s Philosophical Dictionary, under “Councils” he says: “We have already said that in the supplement to the Council of Nicaea it is related that the fathers, being much perplexed to find out which were authentic and which the apocryphal books of the Old and the New Testament, laid them all upon the altar, and the books which they were to reject fell to the ground. What a pity that so fine an ordeal has been lost!”

The publication of Synodicon Vetus in the seventeenth century, and the use of its narrative by Voltaire in his Dictionary, appears to be the origin of the modern myth. Dan Brown did not invent it, but he certainly took advantage of the story and ran with it. Since the advent of the internet, where both truth and falsehood can spread like wildfire and are even harder to tell apart, the “Council of Nicaea chose the books of the Bible” fable is sure to live on. However, when one actually evaluates the evidence of both what happened at Nicaea, as well as how the formation of the biblical canon came together, it is clear that anyone who is interested in the truth can see what did happen at Nicaea, of which had nothing to do with choosing or rejecting Scripture.

Conclusion

The early Christian communities were very concerned with truth—particularly when it came to what God had revealed. Discussions about recognizing (not choosing) the books that God had inspired took place centuries before Nicaea and would continue to be in the discussion for decades after. Nonetheless, what we can decisively see taking place at the Council of Nicaea was the quotation of the New and Old Testament books as authoritative and an acknowledgment of the supremacy and jurisdiction those books held. The participants recognized the rule Scripture possessed as God-breathed and authoritative already, they did not invent the status it held. The twenty-seven books of the New Testament were being read, studied, preached, and declared as God’s holy Word hundreds of years before anyone at Nicaea was even born.

There was no single individual or group that voted the books of Scripture into the Bible. Early Christians saw the authority that certain books held and acknowledged the authority they had. The Bible includes a list of authoritative books rather than being an authoritative list of books. The reliability and recognized inspiration of Scripture span millennia. This does not mean that there weren’t discussions about what was and wasn’t Scripture in the centuries following Christ’s death, there were. The church and its leaders went to painstaking lengths to verify the authenticity and connection of those books to an Apostle or someone who knew an Apostle and it did take time for the dust to settle on the canon of Scripture. But nothing of this process even remotely resembles the Da Vinci Code type narrative that we often hear.

Modern Christians can stand confident and firm in the historical tradition of the church leaders at Nicaea, recognizing Scripture as authoritative, true, and life-changing.

One Bible, many versions

Henry Ford once said, “Any customer can have a car painted in any colour that he [or she] wants, as long as it is black.”1 Before 1881, this was pretty much the situation with the English Bible:2 you could read any English translation of the Bible you wanted, as long as it was the King James Version (KJV). Since 1881, though, things have changed, and a surplus of new translations have been published: The New Revised Version (NRV), New International Version (NIV), English Standard Version (ESV), New Living Translation (NLT), New American Standard Version (NASB), and on and on you can go.

So why are there so many options now? How did the King James get dethroned? Which translation is best for the modern reader? With so many different translations, are any of them actually faithful to the original?

These are all valid questions, and in order to address them, we will need to step back a little to get a “big picture” perspective of the situation. To start, we simply need to ask the question, “Why are there so many English versions of the Bible?”

History of the Text

It is important to understand that there are three basic influences that have given rise to such a wealth of Bible translations over the last hundred years.

First, in 1881, two British scholars by the name of Brook Foss Westcott and Fenton John Anthony Hort published a Greek New Testament established on the most ancient handwritten copies, what are referred to as manuscripts, available to them. This text made many notable deviations from the less ancient Greek text that the King James translators used back in 1611. In the 17th century when the King James Version was being worked on, the amount of documentary sources was limited. The King James translators were using a collection of printed texts that were put together based on the manuscript evidence that was available. The discovery of both more and older manuscripts in the 18th and 19th centuries, however, allowed scholars to map out a clearer picture and create a better understanding of what the original writings, which have been lost to the sands of time, of the New Testament looked like. It wasn’t that the Bible had been lost in any way, but with the uncovering of more ancient Bible copies, it helped to broaden our understanding of how the text of the Bible looked over the last two millennia.

It is also important to understand that, while these earliest copies do get us closer to what the original may have looked like, earlier does not always equate to more reliable. This is where examination of the manuscripts is very important. Scholars don’t assume that an earlier copy is a more reliable copy by nature of it being old. Instead, they carefully examine the manuscript and its text, comparing it to other documents of a similar age and later copies that they think it may be the originator of, and come to an educated decision based on a whole host of factors.

All of this is why some of our earliest manuscripts give us a better picture than what was available in the 17th century. Nonetheless, the Christian faith did stand unshakable for centuries while the earliest copies of its texts lay mostly forgotten in the sands of Egypt. People learned, trusted, valued, copied, and were changed by the Word of God long before the most recent discoveries of our most ancient copies.

However, the older manuscripts, which Wescott and Hort used, did not contain passages such as the longer ending of Mark’s Gospel (Mark 16:9-20), or the story of the woman caught in adultery (John 8:1-11) (for a description of why Mark’s ending stops where it does tap here). But the Greek manuscripts that the KJV translators followed included these and many other extra passages, which were likewise included—for better or for worse—in the KJV.

Shortly following Westcott and Hort’s text, the English Revised Version made its appearance, ushering in a new period of Bible translations, an era based on earlier manuscripts.

Second, since 1895 many discoveries from archaeological digs and manuscript finds have been made, bringing into question some of the renderings and translational choices of the KJV.

In 1895, a German scholar named Adolf Deissmann published a work called Bibelstudien (Bible Studies), which revolutionized New Testament scholarship. He discovered that ancient scraps of papyrus buried in Egyptian garbage dumps contained Greek that was quite similar to the Greek of the New Testament. He concluded that the New Testament was written in the language of the common people. It was not an elitist dialect, as many had previously thought, but rather colloquial Greek, as would have been spoken in the ancient marketplace.

Since Deissmann’s discovery, translators have endeavored to put the New Testament into the language of the average person, creating translations that are comprehensible without compromising the intent of the original language: to speak to ordinary people. Likewise, subsequent discoveries of ancient manuscripts have shed further light on the meaning of many words and phrases in the original Greek, which the KJV translators had only guessed.

Third, there are a great deal of philosophical issues that have influenced subsequent translations. Major contributions in this area have come from missionaries, as they translated the Bible into many indigenous and tribal languages—missionaries translating, for example, a verse like Isaiah 1:18, that says, “Though your sins are like scarlet, they shall be as white as snow,” in an area of the world where snow has never been seen. When Jesus fulfills the prophecy of Zechariah 9:9 and rides into Jerusalem on a donkey, how does one render the text in a location where donkeys do not exist? Is it appropriate to replace the donkey with an alpaca, llama, or gazelle simply for the sake of the reader, or does that do injustice to the words and understanding of the text? These questions of nuance, clarification, and faithfulness in translation both stretched and strengthened translators and their approaches.

The Text of the Modern Translations

During my undergraduate studies, I would routinely talk to the Mormons who frequented my neighbourhood. They were polite and would knock on my door regularly. During one particular conversation, a young Mormon missionary challenged me: “You don’t think your Bible has been changed?” “No,” I replied. “Then who took John 5:4 from your Bible?” he asked, without missing a beat. Puzzled, I turned to the Gospel of John, chapter five, and sure enough, it went from verse 3 straight to verse 5 (for an explanation for why there is no verse 4, tap here). As a Mormon, he would have only read the KJV, which does include this verse.

As I continued to probe, I found even more examples of supposed discrepancies. For example, in 1 Timothy 3:16, in the KJV it says that “God was manifest in the flesh,” but most of the modern translations read, “He who was manifest in the flesh.” At Revelation 22:19, the KJV refers to the “book of life,” while almost all of the modern versions have the “tree of life” in its place. And that was only the beginning: there are hundreds of changes between the KJV and modern translations. So what’s going on?

First, it is important to note that the textual changes in the modern translations effect no major doctrine of the biblical message. The deity of Christ, his virgin conception and birth, salvation by grace alone, and all the rest are still clearly found in the modern translations.

Second, the textual changes in the modern translations are based on comparing the most ancient and most reliable readings from the available manuscripts of the Greek New Testament and Hebrew Old Testament. These manuscripts date from the early second century (AD) and onward (for a discussion of how manuscripts are dated, tap here. The “alterations” we see in our modern text are not a case of “who took John 5:4 out of your Bible?” (as the Mormon missionary asserted) but rather, “who put John 5:4 into your Bible?”

The KJV translators could only use what was available to them: a 1525 Hebrew text and the seven printed versions of the Greek which were based on only six to eight manuscripts (in comparison with the over five thousand New Testament manuscripts we have today). None of those seven manuscripts even came close to the age of the ancient discoveries we now possess. With these older documents, we can get a clearer picture of what the original authors wrote. In the case of John 5:4, we know that this particular text was initially a commentary note in the margin. Over time, the note went from briefly explaining the context of John 5 to making its way into the text itself. For the record, these verses are not missing from your modern translation anyways. In nearly every case you can find a note at the bottom of your Bible explaining the why and what of these “missing” passages. If the KJV translators were alive today, they would of course make use of the plethora of documents we now possess in our undertaking of translating the Bible from its original languages into our own. In fact, they say as much in the preface to the original 1611 King James Bible, that any translation of the Word of God needs to be updated for the purposes of clarity and understanding.

Third, due to the small number of manuscripts then available, there were sections missing from the text. The compiler of these manuscripts, a man named Desiderius Erasmus, had to fill in a great deal of these gaps by translating the Latin Bible back into the Greek. Because of this, some of the phrases that exist in the KJV—such as the “book of life” passage from Revelation 22—are neither found in the majority of manuscripts nor the most ancient manuscripts. But this history gives the shift between words like “book” to “tree” or “God” to “he who” reasonable and understandable explanations. Some were honest mistakes, others were copyist errors, and still others were the well-intentioned, albeit mistaken, efforts of scribes to render the text accurately. At the end of the day, due to the number of manuscripts we now have, we can be confident that our modern translations are accurate readings of what the original authors wrote nearly 2000 years ago.

Word-for-Word, Thought-for-Thought, or Paraphrased?

Translation style also has a big influence on modern translations. Many presume that the more a Bible translation is “word-for-word,” the more faithful it will be to the original text. If the original has a noun in a certain place, they would expect a translated noun to sit in the same position. If the original has ten words in one verse, the translation should ideally have ten words as well. This style of translation is referred to as “formal equivalence,” and is used more often than not in the King James (KJV), the American Standard (ASB/NASB) and the English Standard Version (ESV).

But there are also “thought-for-thought” or “phrase-for-phrase” translations. This translation style is not concerned with replicating grammatical form as much as rendering the intended meaning. This “dynamic equivalence” allows the translation to be more interpretive in order to make the text be easier to understand. This type of translation is reflected in the New International Version (NIV) or the New Living Translation (NLT).

Of course, no single translation is exclusively dynamic or formal equivalence all the way through. Some lean more on one side than the other more often than not, but many modern translations will slide on a scale from book to book, chapter to chapter, and verse to verse, simply for the purpose of making the words readably understandable.

A simple way to check whether the translation of your Bible is more of a word-for-word (formal equivalence) or thought-for-thought (dynamic equivalence) is to turn to Luke 9:44. In this passage, Jesus predicts his betrayal and crucifixion, however, he prefaces his statement with a comment to the disciples:

“Listen carefully to what I am about to tell you…” (NIV)

“Let these words sink into your ears…” (NASB)

The Greek in this passage literally says, “Let these words sink into your ears,” as rendered by the NASB. However, in English we don’t talk like that. What the NIV and other dynamic equivalence translations do is to rephrase this statement with a more understandable English equivalent: “Listen carefully to what I am about to tell you.” The thought-for-thought translator translates for the English reader to easily understand, while staying faithful to the meaning; the word-for-word translator is less concerned about how it sounds in English, prioritizing faithfulness to the form.

When we speak of faithfulness in regard to translation, we need to clarify what we’re talking about. Do we mean faithfulness to form or to meaning? This does not always have a simple answer, for at times when we’re faithful to one, we are not always being faithful to the other. There are certain word-for-word passages in the King James that simply don’t make any sense, and frankly, they didn’t make much sense in 1611 when they were originally translated either. Likewise, many thought-for-thought translations push the line on interpretation and border on saying something the original author did not intend.

Eeny, Meeny, Miny, Moe: Which Translation to Use?

So what does all this mean? Is there any hope for knowing what the original text of the Bible said? Is all lost in translation? Should we conclude that, since there are so many different translations, anyone who doesn’t know Greek or Hebrew can’t possibly understand the text? The answer is a resounding “No!”

Every individual who is serious about Bible study should own at least two different translations: specifically, a thought-for-thought (formal equivalence) translation as well as a phrase-for-phrase (dynamic equivalence) translation. This will help to flesh out the original meaning and the original phrasing for the reader—broadening their understanding of what the text actually says.

Finally, a note must be said regarding the King James Version and modern translations. The King James Bible is a fine translation, and no one should be faulted for using it. However, it is neither the best translation nor the most accurate. And to clarify, the KJV of today is not the KJV of 1611, as it has undergone a number of revisions. The vast majority of KJV Bibles today are either an Oxford or Cambridge printing of a 1769 reprint.3

I am also not saying that all translations are created equal. There exist some “translations” that distort, working not to be authentic to form or meaning, but rather to a specific agenda by the translator(s).

Any sectarian translation is highly suspect. Works done by single individuals often suffer from personal and theological bias (whether intended or unintended) and should therefore, almost always be avoided. The clearest example of a sectarian translation (hardly warranting the title “translation”) is the Jehovah’s Witness’ New World Translation (NWT). Due to the sectarian bias of the JWs in conjunction with the lack of true biblical scholarship among the group, this is easily the worst English translation available. The NWT works to be word-for-word the vast majority of the time, sometimes to an unreadable point. However, when issues of theological questions arise that do not match with JW doctrine, a “phrase-for-phrase” method is enacted that far too often twists the text in an unjustifiable way.

Works done by single individuals also often suffer from personal and theological bias (whether intended or unintended), and should therefore almost always be avoided. Committee translations with multiple individuals have the added benefit of accountability and weeding out any one individual’s personal theological perspective or preconceived bias from bleeding into a rendering of words, phrases, ideas, or concepts within the biblical text. Examples of translations done by single individuals include Moffatt’s, The Living Bible, Kenneth West’s Expanded Translation, and the Berkley New Testament. While these are not necessarily bad translations, and can often be of use alongside committee translations, for personal use it is not always wise to restrict reading to simply these types of Bible versions.

Again, the individual who seeks serious Bible study should take into consideration a multi-translational approach, possessing at least one formal and one dynamic equivalence translation for personal use.

The most important note, however, is that whatever translation you use, read it!

Notes:

(1) Henry Ford and Samuel Crowther, My Life and Work (New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1923), pg. 72.

(2) There were of course, other English translations available such as the Wycliffe Bible (c. 1384), Tyndale Bible (c. 1520s), Coverdale (c. 1520s), the Geneva Bible (c. 1560s), and the Bishop’s Bible (c. 1560s) that all predated the 1611 King James Version.

(3) When many today refer to the Textus Receptus (TR), what they mean is the Trinitarian Bible Society’s Textus Receptus. This, however, is a document compiled by a man named Frederick Henry Scrivener in the mid 1800s. Scrivener compiled the readings that were chosen by the KJV translators and codified them in a single document. It is not based on the manuscripts used by the translators, but rather, their finalized chosen text. In this way, it is a document put together nearly 200 years after the KJV’s final publication in 1611, and represents a Greek New Testament based on an English New Testament based on a Greek New Testament.

(4) For more on the topic of “King James Onlyism,” I would recommend James White’s The King James Only Controversy

Netflix’s Cuties: a social commentary gone awry

By now you’ve probably heard of Netflix’s Cuties (originally titled Mignonnes), a French film released at the beginning of September in North America, that has garnered considerable attention and scrutiny. The criticism comes due to the film’s controversial over-sexual portrayal of the child actors. The original description of the movie read:

The film, which drew attention from politicians and news agencies alike prompted the trending hashtag, #cancelnetflix. The movement was more than just a threat as thousands of subscribers dumped their accounts and Netflix’s stock put up a loss of $9 billion. As the heat cranked up the backlash sparked Netflix itself to make a statement, declaring on their official Twitter account that :

For full transparency I did not watch the whole film. I started out of curiosity but very quickly turned it off. However, due to my desire to want to understand the film (and with the intention of writing this article) I did connect with three individuals who I knew had watched it in its entirety — two who saw its message and outcome as a net positive and one who very strongly denounced the film.

What Cuties gets right

There have been many scathing reviews of the film thus far, many of which I think are warranted in their outrage but might be missing some important points the movie makes. The director of Cuties, Maïmouna Doucouré, in a recent interview explained that her intention with the film was to draw attention to the horrors and dangers of hyper-sexualisation on adolescent women, particularly in the Western world. Many of the articles I read before attempting to watch it myself (and talking to those who had watched it) reduced Cuties to merely a piece of child pornography-light. That I think was not entirely accurate.

There is some genuinely good social commentary within Cuties, touching on the emptiness of modern secular materialism, its over-sexualization of women, as well as the harm and oppression of traditional Islam. Turning the mirror on our own cultures and seeing their ugly blemishes for what they are is always a good thing. Worldview introspectivity is a good practice to exercise.

It seems clear that what Doucouré, as a director from a rampantly secular culture like France, is trying to draw attention to is the oppression that takes place in our cultures both foreign and domestic. As Doucouré notes in her interview,

“Our girls see that the more a woman’s overly sexualized on social media, the more she’s successful. And the children just imitate what they see... It’s dangerous.”

That the over-secularized, hyper-sexualized culture of things like social media can be just as cruel as the fundamentalist Islamic practice of Muslim immigrants. To the extent that this film does that very thing we can see Doucouré’s goal and intention as a noble one.

Source: evanscartoons.com

What Cuties gets terribly terribly wrong

However, please do not misread me — I in no way wish to be an apologist for Cuties and I do not think this movie should have been made. The film ends up doing exactly what it sets out to expose, and while the motives may have been correct the method by which it goes about this task is beyond terrible and results in philosophically sawing off the branch it is sitting on.

The reason for all of the outrage so far is simple: in attempting to point out the over-sexualization and exploitation of children Cuties very clearly over-sexualized and exploited children.

As one of the individual’s who I discussed this film with noted to me, “the gaze of the camera becomes the gaze of the audience,” and the gaze of the camera continually focused on the backsides and crotches of children as they twerked and gyrated. That is not OK. What many of the harsher reviews of this feature get exactly right is that the camera in multiple scenes does indeed focuse and lingers on what the pedophile would go out of their way to look at.

The catch twenty-two of Cuties is that it ends up doing exactly what its author says she is trying to warn against. There is much about the social media saturated, vacuously secularized, and overly-sexualized culture we find ourselves in that needs to be exposed for what it is. But when the cure becomes the disease there is a serious problem. It is a really strange way to stand against the sexualization of eleven year-olds by then making eleven year-olds sexualized.

There are ways to accomplish what Doucouré vocalized as what she was trying to do that would not have taken advantage of and placed the adolescent actors in compromising scenes. In fact, there is a snippet of that very thing within Cuties itself. In one particular scene when Amy, one of the characters in the film, is discovered with the stolen camera of her cousin, she implors for it to be given back to her by offering a seductive dance as payment. The reaction Amy’s cousin gives is horror and confusion. His response is to express how ridiculous and inappropriate Amy is being before he simply walks away. This one scene reveals what the film could have been in its attempt to make an acute social commentary. There are ways that can communicate and suggest that our society has hyper-sexualized eleven year-olds that doesn’t require us to over-sexual eleven year-old actresses in the process.

Where does this leave us?

In decades and centuries past it was common place to teach people, starting with children, catechisms. Traditionally Christian communities would instruct the youngest within the culture with lasting eternal truths. This practice is of course still practiced. I myself when I hear certain phrases can still fill in the answers:

“What is the chief end of man? — to glorify God, and to enjoy him forever.”

”What rule has God given to direct us in how we may glorify and enjoy him? — The Word of God, which is contained in the Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments is the only rule to direct us how we may glorify and enjoy him.

Catechesis is the simple and clear instruction of a teaching that reveals a truth. Christian Catechisms teach profound theological truths in bite-sized snippets. These work not to replace the role of Scripture or Christian education but work as a primer and basis to lead to fuller explanation of the ultimate questions that explain reality around us.

But what is the catechism of our modern secular age? What are the influences we implore on our children that help them to grow into men and women who mature into law abiding, responsible, and acceptable adults? Whether we like it or not our culture is communicating the answers to the existential questions through media. The catechisms of the 21st century western world are the mantras communicated to us by pop music, social media, and political ideology. This is actually an aspect that Cuties diagnoses well in its over-arching commentary on society (both east and west).

But Cuties becomes a victim of its own making. In a culture that pays little attention to consistency and true critical thinking Cuties acts as an example of a secular catechism that attempts to point to a problem. But Cuties plants its feet firmly in mid-air and tries to take a leap, making a true cultural statement by doing the very thing it decries.

In many ways I do not think we should be as shocked by Cuties as we are. Does it objectify and take advantage of children in an appealing and reprehensible way in order to point out the horror of objectification of children? Yes. But in a culture where moral ambiguity is becoming more and more the norm, where ethical decay has taken leaps and bounds within my own life time, Cuties is in many ways the logical outcome of our cultural climate.

Why I date the Gospel of Thomas late

1945 was a year of upheaval — the Allied Forces were pushing through France into the Rhine, the United States Army managed to cross the Siegfried Line, and Soviet soldiers hoisting the red flag over the Reich Chancellery announcing the fall of Berlin. By May of that year the Germans would surrender at Lüneburg Heath, an event that eventually led to the full surrender of the Third Reich and the end of WWII. It is no wonder then that in the midst of such global turbulence, an alleged discovery that same year by an Egyptian farmer named Muhammad ‘Ali al-Samman, went virtually unnoticed. Yet, this discovery of a clay jar filled with ancient manuscripts in Nag Hammadi, Egypt, would later prove to drastically influence the fields of antiquity, religious, biblical, and historical Jesus studies.

What was uncovered would later be referred to as the Nag Hammadi codices, a term that refers to twelve papyrus documents and one tractate that arose on the antiquities market two years after the alleged date of the discovery.

The Nag Hammadi codices in 1948. (Image adapted from Jean Doresse and Togo Mina, “Nouveaux textes gnostiques coptes découvertes en Haute-Egypte: La bibliothèque de Chenoboskion,” Vigiliae Christianae 3 [1949], 129-141, Figure 1; image appears courtesy of the Institute for Antiquity and Christianity Records, Special Collections, Claremont Colleges Library, Claremont, California.)

Found within the contents of this collection was a complete copy of the Gospel of Thomas written in Coptic. While the exact circumstances regarding the discovery by Muhammad Ali are up for scrutiny, one thing is not, the Gospel of Thomas’ introduction changed the landscape for the Christian academy. Helmut Koester and Stephen J. Patterson refer to the Nag Hammadi library surfacing as “the single most important archaeological find of the 20th century for the study of the new Testament” (Koester, The Gospel of Thomas, p. 30). This Coptic text also helped scholars piece together three Oxyrhynchus papyri (P. Oxy 1, 654, and 6554) which had been unearthed before the Nag Hamaddi text and were not definitively known to be the Gospel of Thomas previous to the Nag Hammadi discovery.

What is the Gospel of Thomas?

The Gospel of Thomas is one of, if not the, earliest extant non-canonical Gospel accounts. However, unlike many other Gospels (both biblical and apocryphal) Thomas contains no narrative and only a list of 114 sayings between Jesus and his immediate followers. Many have argued that Thomas deserves to be in the Bible and represents an early sect of Christianity that was merely dismissed by the orthodox Christian church during its time of popularity. Others have pointed to the portrayal of Jesus within the Gospel of Thomas as evidence that Christianity was widely diverse in its beliefs and practice and that what we today call “historical Christianity” is merely the faith of the theological winners of the environment of the first few centuries AD.

When it comes to the composition of this particular document the scholarly community is torn. The majority of scholars place it somewhere in the middle to late second century. A handful of scholars, including John Dominic Crossan and Elaine Pagals, place Thomas within the first century. Yet those who conclude that the Gospel of Thomas precedes the year 100 AD remain a fringe minority.

As note before, Thomas is not a narrative like the canonical Gospels, but rather, a list of sayings that Jesus supposedly said to his immediate disciples. Unlike Jesus being described as “the way, truth, and light” in the biblical Gospels (John 14:6), the Jesus of Thomas is a teacher who reveals the light that exists within us (Thomas 24:3) representing some of the earliest witness to what would later be clearly defined as Christian Gnosticism. The Jesus in Thomas also decries fasting and prayer as evil (Thomas 14:1-3) unlike what we see from the biblical Jesus in places like Matt.4:1-11 or Luke 11:1-28. The Jesus in Thomas mirrors a lot of Greek teachers in Greco-Roman literature rather than a Jewish Rabbi. All of these create a strong disparity between the theology of Thomas and the canonical Gospel canon of Matthew.

Dating Thomas

Dating Thomas becomes tricky due to the internal and external evidence we have for it. We simply lack surviving documentary evidence to conclude anything substantial based on the external artifacts alone. There are only four copies and of those copies the only whole copy that survives today is the famous Coptic manuscript which is part of the Nag Hammadi library, which dates to 340 AD. Our other three copies are Greek fragments that only contain about 20% of Thomas and can be dated somewhere in the neighborhood of 200AD .

When all four manuscripts are examined there is notable textual difference between the full Coptic version and our three Greek fragments. So much so that there appears to have been a remarkable change between the earlier copies we have in Greek and the later version in Coptic. Unlike the minor variation that we see within the text of the New Testament manuscripts, our copies of Thomas have enough overlap to point to them being the same document but the content had clearly adapted over the course of 140 years. As John P. Meier notes in A Marginal Jew,

“[The Gospel of Thomas] may have circulated in more than one form and passed through several stages of redaction.”

Because of this I (and many others) believe that the text of Thomas represents an uncontrolled transmission of a document that adapted between the Egyptian communities that may have wrote it earlier in Greek and then again just over one hundred years later in Coptic. The text of what we know as "The Gospel of Thomas" was not static but had varying renditions, all clear attempts at the same document but one that evolved as a fluid text between the mid second and late third centuries.

Nag Hammadi Codex II, showing the ending of “The Secret Book of John” (Apocryphon of John), and beginning of the Coptic Gospel of Thomas. (Image courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University; and the Egypt Exploration Society and Imaging Papyri Project, University of Oxford.)

The bulk of how Thomas is dated comes from the internal evidence which is harder to do than with other Gospel documents because Thomas’ content is simply a list of sayings that contain no historical references in order to cross-reference potential dates. On top of this Thomas shows little internal coherence outside of catch words and phrases.

However, a noteworthy aspect of Thomas is that it seems very familiar with other books already canonized within our New Testament. The Gospel of Thomas contains quotes or paraphrases from sixteen of the twenty-seven New Testament books. Therefore, a hypothesis that proposes that all of these documents relied on Thomas would force Thomas very very early, potentially in the late 30s or early 40s AD. It is far more probable that Thomas is using the New Testament books as source material rather than the New Testament books relying on Thomas as a point of information supply. In order to prove the latter one would have to push Thomas into the 40s and assume it is already well circulated and popular for all the New Testament authors to make use of it. It is far more probable that a later author made use of the New testament writings, that were already in frequent circulation and popularity within Christian communities by the second century, than it is to try and validate the New Testament authors making use of Thomas.

Richard Bauckham, in his work Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, proposes that Thomas is actually comparing itself with the previous canonical Gospels. Bauckham argues that Thomas is doing this specifically with Matthew and Mark’s Gospel accounts. This is because section thirteen of the Gospel of Thomas has Peter and Matthew trying to guess who Jesus was and failing. The disciple Thomas then steps in and gives the "right" answer. Bauckham argues that using Matthew and Peter in particular (Peter being the source information that the early Church writers like Papias, Clement, Irenaeus, and Tertullian, said Mark wrote his Gospel from), indicates that the Gospel of Thomas is acknowledging and presupposing that he is already aware of the existence of Matthew and Mark (Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses. pgs. 236-237). Likewise, N.T. Wright in The New Testament and the Story of God (pgs. 431-443), notes a smilar theme by pointing that Thomas lacks the identity of the early Jewish community and specifically the early Christian movement that came out of it.

There is also a noticeable connection between all the extant versions of Thomas and particular sects of Syrian Christianity in the mid to late second century. Nicholas Perrin in his paper, Thomas: The Fifth Gospel, analyzed the content of Thomas and translated it into Syriac and Greek and conclude that the phrases and contents of Thomas made more sense when written in Syriac than it did in Greek or Coptic. Specific catchphrases within Thomas are often transliterations of Syriac idioms (nearly 500 of them in total) frequently used within extra-biblical Christian Syriac writing. Craig Evans has noted something similar by stating that,

“[Thomas has] extensive coherence with late-second century Syrian tradition [and a] lack of coherence with pre-70 Jewish Palestine.”

A simple example would be the title of Gospel being attributed to "Didymos Judas Thomas," a title common in Syrian traditions almost exclusively.

Those who date Thomas within the first century do so almost exclusive on its style rather than its content. That is, Thomas is a list of sayings and the narrative style of the canonical Gospels shows development that a sayings Gospel would predate. The problem with this argument is that there are multiple examples of sayings collections that can be traced to the second and third centuries. Rabbinic works like the Chapter of the Fathers or the Sentences of Sextus were both simple lists of sayings that find their origin and dissemination within the second and third centuries.

Closing the book on the Gospel of Thomas

I believe what we see with Thomas is a philosophical syncretism of Gnostic ideas (of which can be placed no later than the early second century) and the Jesus tradition. The Jesus of Thomas is palatable for a gentile audience who would see no problem with the mystic Jesus Thomas portrays. If we try to attempt placing the Gospel of Thomas before the canonical four it makes little sense to then say that the Gospel authors took this Greek philosopher Jesus and proceeded to dress him in Jewish garments. Especially considering that the Christian movement became increasingly more gentile as time went on. In my estimation it would make far more sense to take the Jewish Rabbi Jesus, and dress him up as a Greek mystic philosopher than the other way around.

I do not think the fact that Thomas is simply list of sayings gives us warrant to place Thomas early, never mind as early as the canonical Gospels. Combined with the fact that it seems to fit perfectly within the scope of later Syrian Christian movements, contains Gnostic elements that only started to develop within the second century, paints Jesus more like a Greek philosopher, and its textual fluidity means that the Gospel of Thomas should not and cannot be placed any earlier than 130 AD.

![The Nag Hammadi codices in 1948. (Image adapted from Jean Doresse and Togo Mina, “Nouveaux textes gnostiques coptes découvertes en Haute-Egypte: La bibliothèque de Chenoboskion,” Vigiliae Christianae 3 [1949], 129-141, Figure 1; image appears cour…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a21fbb649fc2b2179ec1ac4/1600789787902-XEFBW5LRNX7UJ5A8KNR9/Screen+Shot+2020-09-22+at+11.49.31+AM.png)